The Best Way to Eat

A single rule to replace all dietary recommendations

One of the many unfortunate lessons taught by the ongoing pandemic is the difficulty of translating rapidly changing, imperfect information into an actionable collective response. When is a mask making a meaningful difference, and when is it simply for show? Are we trying to flatten the curve or eradicate the virus entirely? What level of risk should be acceptable? How do we not only think about these, but change our minds about them as new evidence emerges? How do we then fashion information into either formal policies or informal social norms?

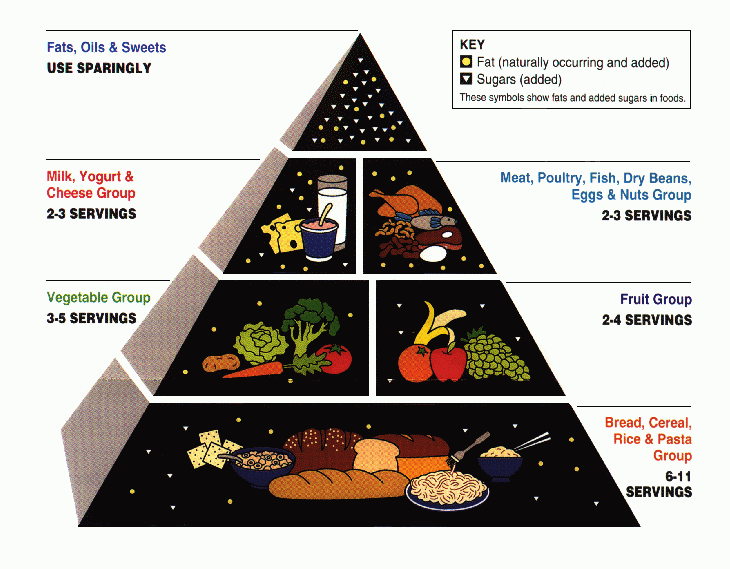

Superficially, our understanding of the relationship between diet and health appears to be the opposite of the crash course in COVID we’ve all been enrolled in for the past couple years. Diet has been the subject of hundreds of thousands of studies. Unlike a novel pathogen, it’s a part of literally every human’s life. We have a remarkably detailed understanding of the intricate processes of metabolism. Over the years there have been various attempts to translate all this knowledge into some sort template for eating, most memorably (at least to people my age) in the form of the food pyramid

A perusal of the food pyramid wikipedia page reveals the changes it has undergone over the years, as well as the various controversies about the whats and the hows of pretty much every aspect of attempts to establish universal dietary guidelines. In all its permutations the pyramid appears to be reasonably simple, until you start thinking about how to actually implement it. Then the details of what constitutes a serving and exactly how much of any one thing (6 to 11 servings of grains?) make it quite tricky to translate into actual meals. Still, that wouldn’t be a big deal if it worked. But the opposite is the case, with rates of diet-related chronic disease steadily rising over the past four decades.

Rather than adhering to a complex, changing program, what if there was one easy to follow rule that could make a meaning difference in public health?

The one ingredient rule

Part of the reason interventions like the Food Pyramid fail likely has to do with the practical difficulties of implementing them, but the other reason is that our understanding of diet and health is actually not so much better than our understanding of COVID, though in the case of diet this is largely due to excess; the endless studies I just mentioned have not created clarity, because many of them are poorly designed or over-interpreted. Just look at the number of diet books and diet blogs out there, all suggesting wildly different things, all with reams of studies to support their position. Look at the way the food pyramid itself has shifted over the years.

This is why I think it would be a good idea to take the biggest step back possible. Instead of wading into the minutiae of portions and proportions, dietary guidelines intended for the public as a whole should be as radically simple as possible; instead of weighing in on the relative merits of meat, dairy, grain, vegetables, fruits, fats, oils, and so on, they should confine themselves to a single, straightforward recommendation.

To the greatest extent possible, people should buy single ingredients – any fruit, any vegetable, any meat, nut, grain, seafood, oil, butter, flour, even sugar. As long as it is a single ingredient, go for it. Take it all home and cook anything. Everything else, from cereal to bread to trail mix or frozen pizza, should be limited.

Yes, it’s arbitrary

Even as I write these words I can hear a swelling chorus of objections. People could just live off of homemade cookies! Beef jerky isn’t unhealthy! Dried fruit would be allowed, and it’s basically candy! Canola oil has too many omega 6 fatty acids and is prone to rancidity! Dark chocolate is fine! No one will get enough fiber! Scurvy! Pellagra! Rickets!

I agree with quite a few of these concerns. It would be possible to eat an unhealthy, entirely from scratch diet. But any universal rule should be both modest, so that it does not need to be continuously updated, and simple, so that even people who don’t have the time or interest to delve into the seamy underbelly of nutritional science can attempt to follow it.

The point of the one ingredient rule would be to reduce the consumption of processed foods. Only a vanishingly small number of people would attempt to follow it perfectly, just as almost no one actually peruses My Plate before going shopping. The aim would be directional, to shift on average some proportion of foods from more processed to less processed. There isn’t much certainty in the world of nutrition, but this is one of the few trends I’m confident would be a positive.

Predictable issues

While I do think the one ingredient rule would be more likely than the food pyramid to improve public health in the aggregate, I can’t delude myself into thinking it would be a panacea. First, cooking most meals at home would require time that many people don’t have. As of 2012 half of food dollars in America were spent on food prepared away from home, providing one third of calories. And that’s just restaurant food. These figures do not include chips, frozen meals, cereal, or any of the other processed foods that can be bought at the store and brought home. While some of these choices likely have to do with convenience, they also reflect the time crunch most of us feel.

Another problem would be implementing it. Who would actually want to promote this message? Certainly not the food industry, the business model of which largely relies on processing basic foods into novel products. Not nutritionists, who would have to subordinate their individual views on the benefits of one diet over another to a simple, sustained message. Certainly not the restaurant industry, which would suffer if more people started eating at home.

A healthy culture

Still, I can’t shake the idea that it would be a huge improvement. As I’ve made clear, I do think it would benefit public health. But it also might promote less overthinking about food. Rather than trying make food choices fit into a convoluted system, the approach to food would be of cooking, eating, and hopefully enjoying, without so much thought about chasing one nutrient or avoiding another.

It would also sidestep the endless fights about the optimum diet. Anyone who cared to for health or other reasons could follow a vegan, a carnivore, paleo, or Mediterranean diet without straying from the one big idea.