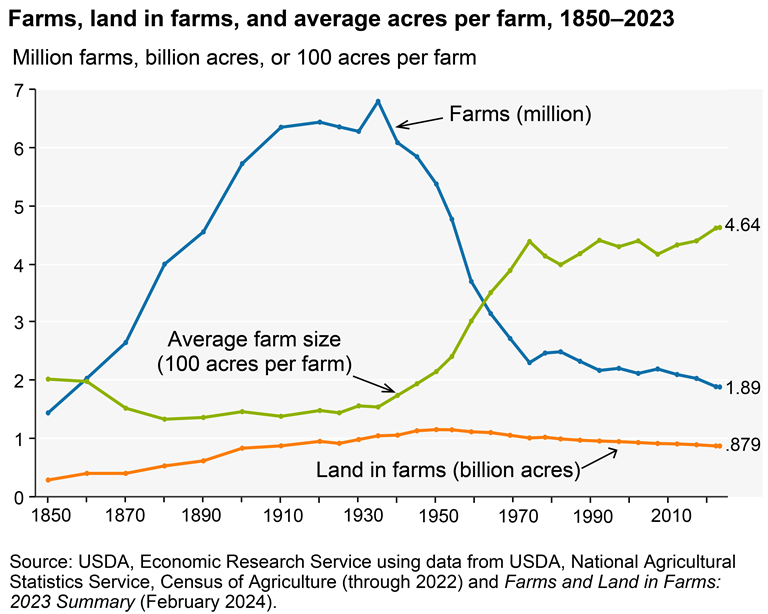

Between 2017 and 2022 New York lost 2788 farms, a more than 8% decline. It was concentrated in small farms; the number of operations with over 500 acres actually increased. In other words, many of the small farms were absorbed by the larger. What’s happening in New York reflects a long term national trend of fewer farms generally, fewer small farms in particular, and growth only in the largest of farms, as they take over more and more land.

But is this consolidation a problem?

Many agronomists argue that it’s actually a positive. Even with the recent uptick in food costs, Americans spend on average 11% of their income on food, far less than the historic norm. And when you consider that much of the cost is food away from home (food from restaurants, convenience stores, and so on, which is much more expensive than the raw ingredients) the actual cost of getting enough calories to eat is lower than basically any other time or place in human history.

While cheap food isn’t entirely due to consolidation, big farms, particularly those producing an ocean of corn and soy, have played an integral role in reducing costs on the supermarket shelf. The efficiencies made possible by working huge acreages with giant machines have been passed onto the consumer in the form of low prices.

I don’t want to sell this short. The first job of a food system is to provide the populace with enough calories and to make them widely available. But the downsides are also obvious, from environmental degradation to the toll on human health. When cheapness is the only concern, a lot of important things get neglected.

But I want to point out a couple of the subtler costs. While there’s nothing magical about small farms — there are good small farms and bad small farms — their disappearance fundamentally changes the character of rural communities. Small farms can promote a sort of social cohesion that large farms cannot

It’s easy to see how, in an urban context, people look out for each other, how the shop owner knows the local parents and can tell them when mischief is afoot, for example. Despite the lower density, there’s a similar willingness to lend a hand in rural areas. Just a few weeks ago some of our new cows escaped, and it was our farming neighbors who helped round them up. The disintegration of soft social ties like neighborliness have a variety of causes, but in rural America the loss of small farms is a major contributor.

I suspect it also heightens the divides between rural and urban people. More small farms necessarily means more people having a personal connection to the land, even if it’s via a cousin or uncle or friend. I know from experience that people enjoy visiting farms, particularly people who don’t live on them. (Actually, that might not be right. Farmers often love visiting other farms too.)

The truth is that, more than the pragmatic and social problems that follow from it, the loss of small farms makes me sad. I like the way they make the land look, and I like seeing people and livestock out in the world far more than I like seeing corn monocultures and giant tractors. I like real food more than cheap, convenient boxes of calories. It seems to me that there’s a point at which the world becomes too efficient for human life, and we would do well to think about where it is.

2 comments

I’m not sure I believe it.

Locally, (I’m near Cobleskill), the number of small farms has increased five-fold in 5 years.

This is almost entirely due to a burgeoning community of old-order Amish.

The average family size is a jaw-dropping 8 kids per family, and every one of them is going to want his own small farm. This in turn helps “English” small farms (like mine) survive, as one can make a solid living selling them hay and other things that they have a hard time producing without tractors.

Moreover, I see this happening all over the state, with new communities popping up faster than I can keep track.

This observation is not consistent with the statistic you cited.

Critically, the Amish do not fill out that ag census I get every year, so the folks who watch such things may just simply not be counting them.

On a different note, I think the vaunted efficiency of the “big tractor” farms is both overstated and overated. I’d bet most of them would be out of business within 10 years without crop insurance and other forms of taxpayer-provided capital injections.

I recently watched a Netflix documentary – You Are What You Eat: A Twin Experiment. I was hooked because the architecture of the study aligned with what I believe is salubrious for both humans and the planet. Sadly, I soon realized that the show was to be a tantara for a vegan lifestyle. I mention this myopic production because, when questioned, most people did not care where their food comes from as long as it tastes good. I was so nettled by this lack of awareness. I am dismayed that I feel it would prove otiose to modulate their behavior from consumer for self to steward of the earth. I am left with only a resolution to support farms such as yours.