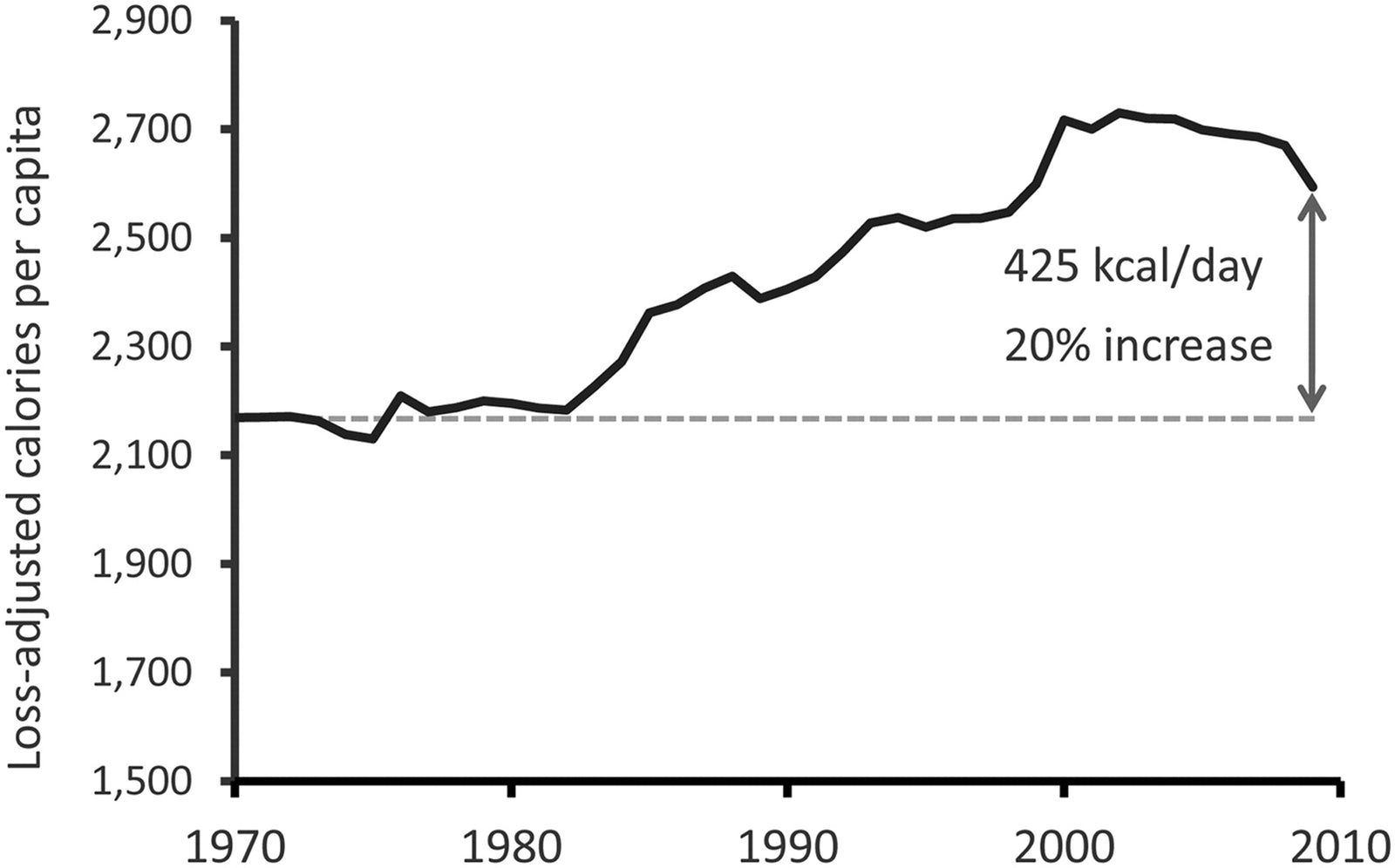

The idea that weight gain occurs when a person eats more calories than they burn and loses weight when they burn more calories than they eat is obviously true; gaining weight requires an energy surplus, while losing weight requires an energy deficit. If you look at the chart above you’ll see that from 1970 to 2010 average energy intake in the US increased by over 400 calories per day. (Frustratingly, the USDA data is incomplete for the last decade.) This maps quite nicely onto rising rates of obesity and associated diseases, such as type 2 diabetes (page 3). Taken together, these data support the idea that weight gain is caused by eating an excess of calories. But I hope I can convince you that this formulation — calories in, calories out — is both obviously true and completely useless.

It’s useless because it contains no why. That is, why do we, on average, eat more calories than we burn, and why are more of us eating more than we did a few decades ago? The most popular, and most obviously wrong response, attributes it to willpower. That is, once we know weight gain is caused by consuming excess calories, we can simply choose to eat less. For this to be the primary driver of changes in dietary habits we’d need to believe some remarkable things: first, that our grandparents, on average, had far more willpower than we do, that they would have had similar rates of obesity but for constant mealtime vigilance, and further, that members of basically all cultures had a similar capacity for self-regulation which also began to mysteriously decline as soon as they were exposed to a modern food system.

This has it exactly backwards; humans have not changed, or not nearly so much as our surroundings have. It is not that we used to have more willpower. If willpower plays a role at all, it’s that our willpower is subjected to far greater challenges than in previous times. But whether or not you like the idea of willpower, it’s clear that an environmental change is the most likely culprit. And this is where it gets tricky, since observing that something has changed in our food system broadly still does not tell us what or why with enough specificity to chart a path forward.

One possible answer is food palatability, most prominently championed by Stephan Guyunet in his book The Hungry Brain, though this article, also by Guyenet, offers a more concise examination.

Here’s how he describes the concept:

Relevant food properties include caloric density and texture as well as the content of fat, starch, simple sugars, salt and free glutamate; under certain conditions, these factors can influence food intake and body fatness. In addition, a variety of other cues can be associated with these factors and become rewarding over time, resulting in acquired preferences. Palatability is defined as the pleasure or hedonic value associated with food, and it has been consistently shown to influence meal size in humans.

To put it in simpler terms, there are combinations of qualities, including sugar or other simple carbs, fat, saltiness, and caloric density, that make some foods more pleasurable to eat than others. Because they are more pleasurable, we eat more of them. I’m not going to go down the rabbit hole of proposed neurochemical and physiological feedback loops that might be triggered by persistent exposure to highly palatable food, because these are complex and largely speculative, but the basic idea is pretty straightforward.

Think of it this way. You could eat a baked potato plain, with absolutely nothing added. If you were hungry you’d probably finish it, but you most likely wouldn’t be craving more. You could also eat one or two tablespoons of plain butter, but it’s unlikely you’d be looking forward to tablespoon number three. However, if you put a baked potato and butter together, you have a food that is much more enjoyable to eat than either ingredient on its own, one that you’ll have an easier time eating more of. You will consume more calories of potato and butter together than of potato and butter separately. And that’s an anodyne example. Doritos, doughnuts, and manifold other products of the modern food system have been far more exquisitely engineered for deliciousness than even a baked potato with butter.

This makes intuitive sense, but I want to urge caution. First, the fact that people will readily eat more of one food than another in a single sitting does not necessarily translate to the long term. After stuffing yourself on baked potatoes with butter at lunch, without any conscious awareness you might eat less at dinner. The studies that purport to show that overeating continues, that there is a long term causal link between food palatability and weight gain, at least the ones I could find, were conducted on rats in controlled laboratory conditions, not people living normal lives.

Second, I wonder how unpalatable food used to be. I’ve heard Guyenet advocate for eating very bland food as a possible antidote to excessively palatable modern foods, but I wonder what the basis for this idea is. It strikes me as so unpleasant that few people will be able to adhere to it long term, and I don’t think food in the past was especially bland as a rule. I have a 1943 edition of The Joy of Cooking, which makes it pretty clear that people have long known that combinations of fat and carbs can be delicious. Last week I mentioned my neighbor Don, but this week I’m thinking of Homer, who lived on the next farm over and who swore his mom baked two different pies every single day when he was growing up. Is the widespread availability of palatable food really a new phenomenon?

But the biggest problem is assessing palatability at all. In all my poking around for an actual list of foods ranked by palatability I came up with remarkably little. The best I’ve found is appendix 3A of this paper. (It also gives each food a healthfulness score, but please, please ignore that. It’s worthless.) While candy seems to score extremely high on the palatability index, everything else is a mess. Puffed rice cereal is more palatable than a quesadilla with meat and cheese. Coleslaw is far more palatable than a cheeseburger. Fresh pineapple gets a negative score for palatability, which makes sense to me, since I hate the stuff, but fresh raspberries score even worse, as does orange juice. Plain hot dogs are more palatable than pigs in a blanket. Dry salami is more palatable than a Snickers bar. Who would take this seriously? How would you begin to formulate either public policy or a personal diet plan around such an incoherent ranking?

I’m left in a difficult place. The idea that the availability and composition of foods in modern life and the consumption patterns they encourage are at the root of increasing obesity makes lots of sense, as does the idea that they are altering the way in which brain and the body regulate weight and appetite through various not well understood feedback loops.

Instead of saying “we gain weight because we consume more calories than we burn” it’s saying something like, “the variety and availability of certain modern foods, particularly solid foods that have a combination of fat and carbohydrate and less water, as well as sugary drinks, rewire many of our brains to eat more food than we would in a food environment without these options, while also changing out bodies to have a higher default weight.”

If forced to guess I’d say that’s most likely approximately right, though I am also open to the idea that changing levels of physical activity might also be a significant contributor, and I haven’t entirely dismissed the idea that certain additives or preservatives could play a role in metabolic dysregulation, though the evidence I’ve seen is weaker. But “guessing this is approximately right” is quite a bit different from believing it to be supported by rock solid evidence. Indeed, it contains so many variables that there is no conceivable way to put it to the sort of clinical trial that would begin to prove or disprove it, and the existing evidence for the very notion of palatability as a useful metric isn’t particularly compelling.

In the end, I land in much the same place I did when thinking about dietary recommendations. It is manifestly clear that something, or some combination of things, in the modern food system is completely broken, but just what that or those might be remains maddeningly hard to figure out with any certainty.

Here’s a tangent all this has me thinking about. In recent weeks there’s been quite a bit of news coverage of the failures of plant based meat alternatives. People simply aren’t buying that many of them, despite lots of advertising and high profile partnerships with existing brands.

It’s probably a moot point — companies like Impossible Foods must have food scientists who do nothing but make their products as delicious as possible — yet I still wonder if anyone has set out to make a veggie based meat substitute that is radically more palatable than meat when eaten in a similar context. Forget about healthfulness, forget about nutritional profile entirely, just make the most delicious disk of textured pea protein imaginable. It’s an interesting thought, but I don’t anticipate launching Cairncrest Meatless Crumbles anytime soon.

P.S. If you know of a better index of food palatability, particularly if it includes plain meat, please let me know.