The Focus on Lead

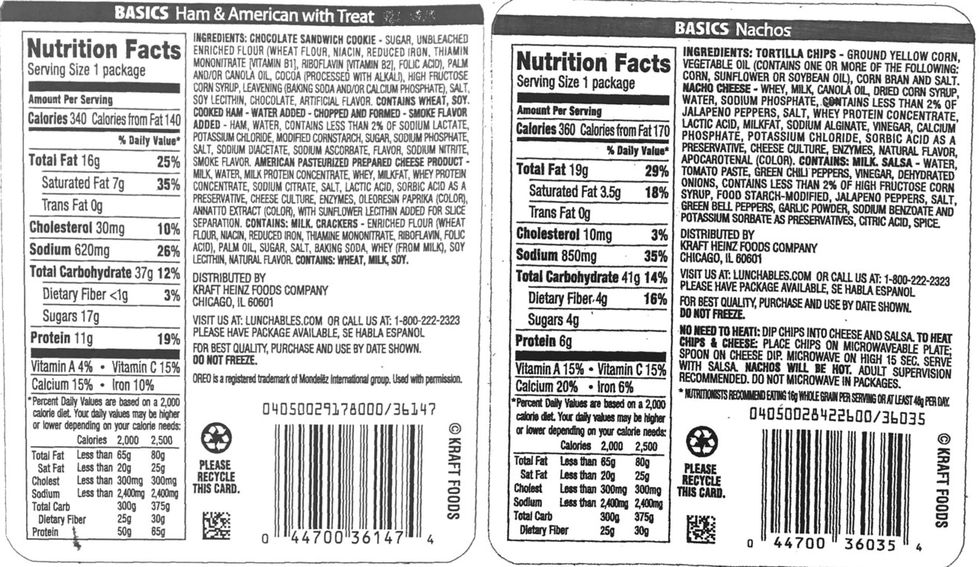

A recent study by Consumer Reports found elevated, though not illegal, levels of lead and cadmium in prepackaged lunch meals. Lunchables is the most famous version, but tests of similar products produced by other companies yielded the same results. Elevated sodium was also present, which will be no surprise to anyone familiar with what crackers, ham, and cheese taste like. Except for one, all of the tested products also contained phthalates, a class of chemicals that includes BPA.

Understandably, most coverage of the report has focused on the presence of heavy metals in food marketed as the ideal school lunch. While there are legal limits on lead, these are a matter of expediency; there is no known level at which lead is actually safe, particularly for children. But it is so ubiquitous that it can’t be completely avoided, so we all try to minimize contact with it and go on with our lives.

The Potential Dangers of Phthalates in Premade Lunches

But I fear this is also a case of focusing on what we can measure and downplaying what we cannot. The presence of phthalates makes me curious about the concentration of microplastics in these premade lunches. The two are often found together, but I haven’t seen any studies that directly correlate them. Because methods to detect microplastics are only now being developed, the hard work of trying to figure out where they are, let alone their impact on human health, has only begun.

Nevertheless, there are reasons for concern. The most obvious is that BPA and similar compounds might be disrupting our hormonal systems. While the effect of any one of these chemicals is small, and while we generally only encounter them in small amounts, we do so throughout our lives. It’s easy to imagine an effect that, while smaller than that of smoking or lead, is still real and negative. But this sort of impact, caused by prolonged exposure to trace amounts of something, is devilishly difficult to prove.

The second potential problem has to do with microplastics themselves. That is, what happens when we have tiny particles of plastic lodged inside us? This question is even less studied than chemical exposure, but one early attempt to examine it has potentially implicated microplastics in worse cardiovascular outcomes.

Perhaps the coming years will provide clarity. I’m more optimistic on the question of microplastics than of the chemicals that often accompany them, but I doubt we will have much certainty about either. We can be confident about the negative impacts of lead exposure because they are so profound that even blunt tools like epidemiology can persuasively demonstrate harm. If such ironclad evidence exists about microplastics, I haven’t seen it.

Humility Need Not Mean Apathy

On the one hand, it is good news that microplastics and their associated chemicals probably aren’t as dangerous as lead. On the other, it makes them tricky to think about. How hard should we work to avoid them? What does it mean that, as a result of modernity, they are proliferating throughout the environment and our food.

While we should have humility and curiosity in answering these questions, it strikes me as entirely reasonable to try to avoid microplastics when possible, especially in foods designed for and marketed to children. Figuring out how to build a healthier food system from the ground up is a project that will take decades, but avoiding the worst products of the current system is still a worthwhile goal.